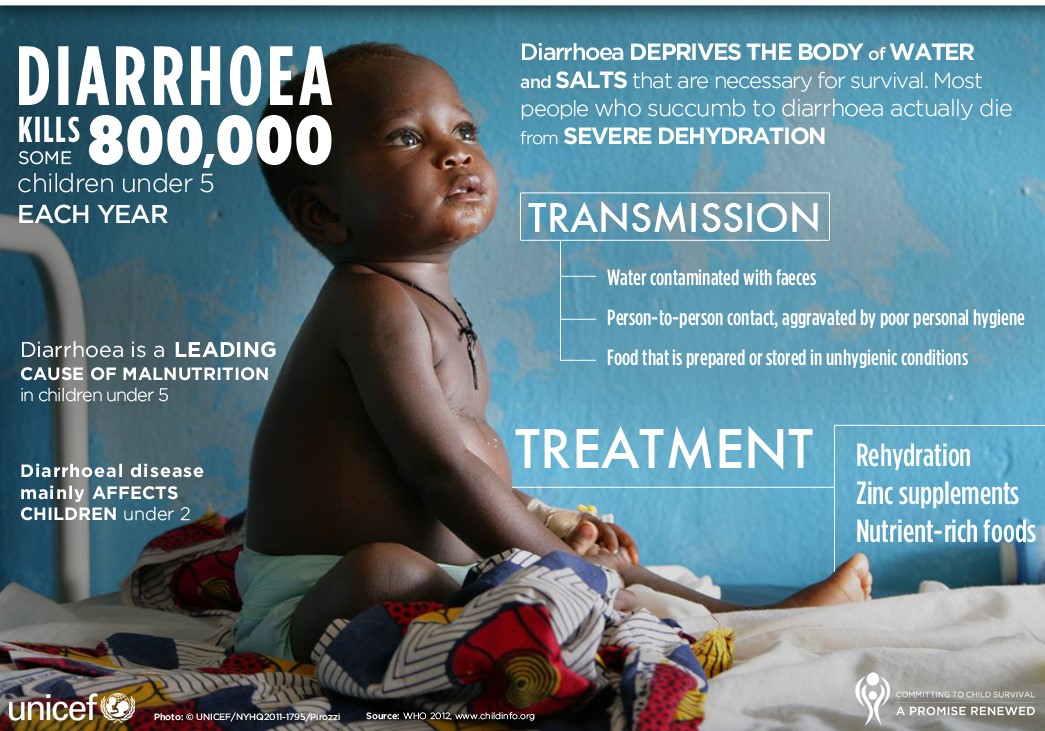

Replacement of fluid and electrolytes orally can be achieved by giving oral rehydration salts (solutions containing sodium, potassium, citrate and glucose). Acute diarrhoea in children should always be treated with oral rehydration solution (ORS) and zinc according to WHO recommended plan A, B, or C as shown below.

WHO guideline for the classification of dehydration and recommended treatment regimen

NO DEHYDRATION – Treatment Plan A (see below)

- Appearance: Well, alert

- Eyes: Normal

- Thirst: Drinks normally, not thirsty

- Skin pinch: Goes back quickly (<1 second)

MODERATE DEHYDRATION – Treatment Plan B (see below)

- Appearance: Restless, irritable

- Eyes: Sunken

- Thirst: Thirsty, drinks eagerly

- Skin pinch: Goes back slowly (1 second)

SEVERE DEHYDRATION – Treatment Plan C (see below)

- Appearance: Lethargic, or unconscious; floppy

- Eyes: Very sunken

- Thirst: Drinks poorly or not able to drink

- Skin pinch: Goes back very slowly (≥2 seconds)

Recommendations for managing acute diarrhoea (without blood)

The objectives of treatment are to:

- prevent dehydration, if there are no signs of dehydration;

- treat dehydration, when it is present;

- prevent nutritional damage, by feeding during and after diarrhoea; and

- reduce the duration and severity of diarrhoea, and the occurrence of future episodes, by giving supplemental zinc.

These objectives can be achieved by following the WHO recommended treatment plan A, B, or C depending on the degree of dehydration.

Treatment Plan A: NO DEHYDRATION. Children with no signs of dehydration need extra fluids and salt to replace their losses of water and electrolytes due to diarrhoea. These measures are essential to prevent dehydration. Explain to the parents the importance of giving the child more fluids than usual to prevent dehydration and continuing to feed the child to prevent malnutrition at home. They should also be advised about circumstances in which they should seek further advice or take the child to a health worker. These steps are summarized in the four rules of Treatment Plan A:

Rule 1: Give the child more fluids than usual, to prevent dehydration. Suitable fluids include at least one fluid that normally contains salt (e.g. ORS solution, salted drinks including salted rice water and vegetable or chicken soup with salt); Fluids that do NOT contain salt (e.g. unsalted soup, unsalted rice water, yoghurt or plain water). Give as much fluid as the child wants until diarrhoea stops and, as a guide, after each loose stool give:

- Child (<2 years): 50–100 mL (a quarter to half a large cup) of fluid;

- Child (2–10 years): 100–200 mL (a half to one large cup);

- Child (> 10 years): Give as much fluid as the child wants

Rule 2: Give supplemental Zinc (10 – 20 mg) to the child, every day for 10 to 14 days.

- Infant (<6 months): 10 mg (elemental zinc) daily for 10–14 days.

- Infant or Child (>6 months): 20 mg (elemental zinc) daily for 10–14 days.

Giving zinc as soon as diarrhoea starts helps to reduce the duration and severity of the episode as well as the risk of dehydration. Continuing zinc supplementation for 10 to 14 days helps to fully replace the zinc lost during diarrhoea and also reduces the risk of the child having new episodes of diarrhoea in the following 2 to 3 months.

Rule 3: Continue to feed the child, to prevent malnutrition. The aim is to give as much nutrient-rich food as the child will accept. Breastfeeding should always be continued to reduce the risk of diminishing supply.

Rule 4: Take the child to a health worker if there are signs of dehydration or other problems.

The mother should take her child to a health worker if the child: starts to pass many watery stools; has repeated vomiting; becomes very thirsty; is eating or drinking poorly; develops a fever; has blood in the stool, or the child does not get better in three days.

Treatment Plan B: MODERATE DEHYDRATION. Children with some dehydration should receive oral rehydration therapy (ORT) with ORS solution in a health facility following Treatment Plan B. Whatever the child’s age, a 4-hour treatment plan is applied to avoid short-term problems.

Administer approximately 75 mL/kg of ORS in the first 4 hours:

- Below 4 months (or <5 kg): 200–400 mL

- 4–11 months (or 5–7.9 kg): 400–600 mL

- 12–23 months (or 8–10.9 kg): 600–800 mL

- To 4 years (or 11–15.9 kg): 800–1,200 mL

- To 14 years (or 16–29.9 kg): 1,200–2,200 mL

- 15 years or older (or 30 kg and above): 2,200–4,000 mL

NOTE:

- The amount of ORS solution needed for rehydration is calculated based on the child’s weight. Use the patient’s age only when the weight is not known. The amount may also be estimated by multiplying the child’s weight in kg times 75 mL.

- A larger amount of solution (Child up to 20 mL/kg/hour and Adult up to 750 mL/hour) can be given if the patient continues to have frequent stools or wants more than the estimated amount of ORS solution, and there are no signs of overhydration (e.g. oedematous eyelids).

- Show the mother how to give ORS solution, a teaspoonful every 1-2 minutes for a child <2 years.

- In case of vomiting, rehydration must be discontinued for 10 minutes and then resumed at a slower rate.

- Check the child’s eyelids. Edematous (puffy) eyelids are a sign of overhydration. If this occurs, stop giving ORS solution, but give breast milk or plain water, and food. Do not give a diuretic. When oedema has gone, resume giving ORS solution or home fluids according to Treatment Plan A.

- In younger children, breastfeeding should be continued on demand and the mother should be encouraged to do so; older children should receive milk and nutritious food as normal after completing the 4-hour oral rehydration.

- Begin to give zinc supplementation, as in Treatment Plan A, as soon the child is able to eat and has completed 4 hours of rehydration.

- After 4 hours, reassess the child’s status (look for signs of dehydration) to decide on the most appropriate subsequent treatment:

- Severe dehydration: If signs of severe dehydration have appeared, IV therapy should be started following WHO Treatment Plan C. This is very unusual, however, occurring only in children who drink ORS solution poorly and pass large watery stools frequently during the rehydration period.

- Moderate dehydration: If the child still has signs indicating some dehydration, continue oral rehydration therapy by repeating the treatment described above. At the same time, start to offer food, milk and other fluids, as described in WHO Treatment Plan A, and continue to reassess the child frequently.

- No dehydration: Oral rehydration solution should continue to be offered once dehydration has been controlled, for as long as the child continues to have diarrhoea. Teach the mother the 4 rules of home treatment.

Treatment Plan C: SEVERE DEHYDRATION. Hospitalization is necessary, but the most urgent priority is to start rehydration. The preferred treatment for children with severe dehydration is rapid intravenous rehydration. In hospital (or elsewhere), if the child can drink, oral rehydration solution should be given during the intravenous rehydration (20 mL/kg/hour by mouth before infusion, then 5 mL/kg/hour by mouth during intravenous rehydration). For intravenous rehydration, it is recommended that compound solution of sodium lactate (or, if this is unavailable, sodium chloride 0.9% intravenous infusion) is administered at a rate adapted to the child’s age.

Intravenous rehydration using compound sodium lactate solution or sodium chloride 0.9% infusion

By IV:

Infant: 30 mL/kg over 1 hour, then 14 mL/kg/hour for 5 hours.

Child: 30 mL/kg over 30 minutes, then 28 mL/kg/hour for 2.5 hours.

If the intravenous route is unavailable, a nasogastric tube is also suitable for administering oral rehydration solution.

Nasogastric rehydration using oral rehydration solution

By Nasogastric tube:

Infant or Child: 20 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours (total 120 mL/kg).

If the child vomits, the rate of administration of the oral solution should be reduced. Reassess the child’s status after 3 hours (6 hours for infants) and continue treatment as appropriate with plan A, B or C.

For further reading:

- Clinical management of acute diarrhoea – WHO/UNICEF Joint Statement [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 7]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/68627/WHO_FCH_CAH_04.7.pdf;jsessionid=D2C22C5302AE0608A54856E90A043334?sequence=1

- MNCH Commodities-OralRehydration.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 5]. Available from: https://www.ghsupplychain.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/MNCH%20Commodities-OralRehydration.pdf

- WHO Model Formulary for Children 2010. Based on the Second Model List of Essential Medicines for Children 2009 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 6]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js17151e/

- WHOdiarrheaTreatmentENGL1.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 6]. Available from: http://www.zinctaskforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/WHOdiarrheaTreatmentENGL1.pdf