The management of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) changed drastically following discovery that the damage to the joints was already well underway within the first year of the disease. This finding forms the basis of the current mainstay of pharmacological treatment of RA which is the Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs otherwise known as DMARDs. These drugs essentially work by suppressing the body’s inflammatory response to the disease, hence the term “disease-modifying’. They suppress the action of B and T cells which are responsible for the processes that lead to the progress of symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis; they also slow down joint damage.

Early commencement of DMARD therapy has been found to be more successful than other less intensive strategies. Currently, combination therapies of 2 or more DMARDs have been shown to produce better results versus monotherapy. Although this is not true for all DMARD combinations, combination therapies such as methotrexate and cyclosporine have produced better disease control and more sustainable outcomes than monotherapy with methotrexate alone for example.

The risk for toxicity using conventional DMARDs however remains a challenge (especially when using combination therapy as this could potentially double the risk of toxicity). Methotrexate levels have to be carefully watched in patients on monotherapy for example due to the risks of bone marrow toxicity. This has led to the development of newer DMARDs with a broader therapeutic index. Leflunomide (LEF) is a new DMARD that decreases rheumatoid inflammation by inhibiting pyrimidine synthesis. It shows similar efficacy as methotrexate but lower levels of toxicity. Etanercept and Infliximab are also examples of emerging biologic DMARDs that show low toxicity however consensus for their use alone is still undecided and usually delayed till at least one non-biologic DMARD has been used without sufficient results.

Similarly, the previous mainstay for management of inflammatory responses in RA was the Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), but prolonged use of NSAIDs posed the risk of GI toxicity as well as nephrotoxicity. The mode of action of NSAIDs involves non-specific inhibition of cyclooxygenase and subsequent production of inflammatory factors; this non-specific inhibition (of both COX-1 and COX-2 prostaglandins) is also responsible for the toxicity of NSAIDs. Inhibition of the COX-1 pathway decreases the production of prostaglandin G2 and H2 which are needed for GI protection aside from their inflammatory responses. Newly developed agent celecoxib can selectively inhibit the COX-2 pathway alone while sparing COX-1 and hence, reducing the adverse effects associated with traditional NSAIDs. Although these new agents are not proven to offer better results than NSAIDs, they are less toxic and recommended for RA patients at risk of GI bleeding or in place of prolonged NSAID use.

So how do you know when to initiate monotherapy or combination DMARD therapy? How do you determine the correct combination therapy for RA management? The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) developed recommendations and algorithms for use of non-biologic and biologic DMARDs for patients with RA.

In the updated 2012 report, for early RA (<6 months), DMARD monotherapy is recommended in cases with low and moderate disease activity without features of poor prognosis (such as functional limitation and extra-articular disease). In moderate disease activity with features of poor prognosis, double or triple combination DMARD therapy should be used. Patients with high disease activity without features of poor prognosis should be commenced on DMARD monotherapy or a combination of Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and Methotrexate (MTX). In high disease activity with features of poor prognosis, commence an Anti-TNF with or without methotrexate or double or triple combination DMARD therapy. See the Legend under the algorithm below for the DMARD combination regimens.

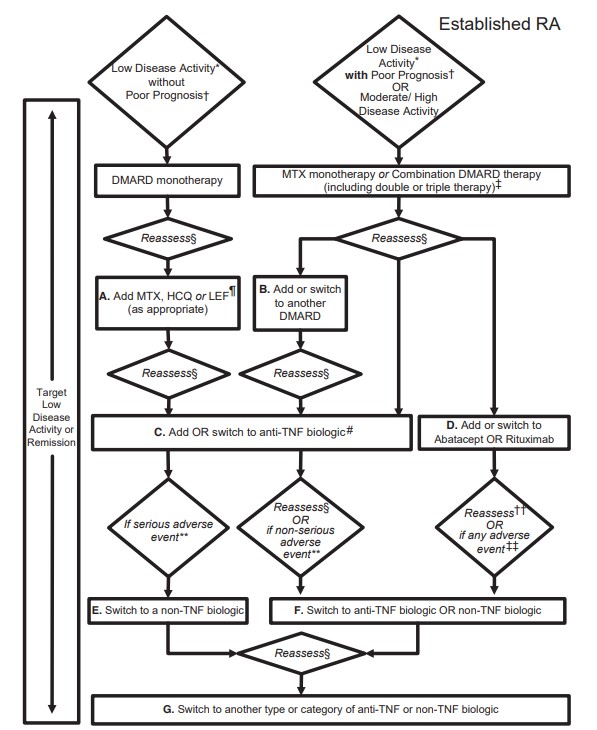

The management of long-standing or established RA (6 months or more) requires a more detailed process as highlighted in the algorithm below:

‡ Combination DMARD therapy with 2 DMARDs, which is most commonly MTX based, with few exceptions (e.g., MTX + HCQ, MTX + LEF, MTX + sulfasalazine, sulfasalazine + HCQ), and triple therapy (MTX + HCQ + sulfasalazine).

§ Reassess after 3 months and proceed with escalating therapy if moderate or high disease activity in all instances except after treatment with a non-TNF biologic (rectangle D), where reassessment is recommended at 6 months due to a longer anticipated time for peak effect.

¶ LEF can be added in patients with low disease activity after 3– 6 months of minocycline, HCQ, MTX, or sulfasalazine.

If after 3 months of intensified DMARD combination therapy or after a second DMARD has failed, the option is to add or switch to an anti-TNF biologic.

** Serious adverse events were defined per the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA; see below); all other adverse events were considered nonserious adverse events.

†† Reassessment after treatment with a non-TNF biologic is recommended at 6 months due to anticipation that a longer time to peak effect is needed for non-TNF compared to anti-TNF biologics.

‡‡ Any adverse event was defined as per the US FDA as any undesirable experience associated with the use of a medical product in a patient. The FDA definition of serious adverse event includes death, life-threatening event, initial or prolonged hospitalization, disability, congenital anomaly, or an adverse event requiring intervention to prevent permanent impairment or damage

The development of new DMARDs as well as selective COX-2 inhibitors open up new frontiers in RA management and provide new opportunities for better management. The eventual management process and decision on DMARD therapy depend on the duration of the disease and progression; new frontiers are currently being explored in TNF inhibitors amongst others.

References:

- St Clair EW (1999). Therapy of Rheumatoid Arthritis: New Developments and Trends. Current Rheumatology Reports, 1(2) 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-999-0012-6

- Schuna, A. A. & Megeff, C. (2000). New drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacists, 57(3), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/57.3.225–

- 2012 Update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology Recommendations for the Use of Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs and Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis ( Jasvinder A. Singh et al). Arthritis Care & Research Vol. 64, No. 5, May 2012, pp 625– 639 DOI 10.1002/acr.21641