Excerpts from WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria 2015 & Nigeria’s National Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Malaria (FMOH, 2015)

Introduction

The World Malaria Index 2017 depicts a grim profile of Nigeria with 76% of the population living in high (>1 case per 1000 population) and 24% in low (0-1 cases per 1000 population) transmission areas. The country accounts for about 25% of estimated malaria cases globally and the highest proportion of malaria-related mortality based on WHO estimates. Pregnant women and children are especially vulnerable.

Nigeria’s 3T (Test, Treat and Track) approach to malaria case management is in line with WHO recommendation and is embodied in the National Malaria Strategic Plan (NMSP) 2014-2020. The objectives are:

- Test all suspected cases of malaria using Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDT) or microscopy,

- Treat promptly with recommended artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) if the result is positive, and

- Document

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium. It is spread mainly from the bite of female Anopheles mosquitoes which usually occurs between dusk and dawn. Less common modes of transmission include blood transfusion, organ transplant, use of contaminated needles & syringes, and mother-to-child transmission.

There are 5 known species of Plasmodium that can cause malaria in humans:

- P. falciparum

- P. vivax

- P. ovale

- P. malariae and

- P. knowlesi

P. falciparum causes the most severe infections and accounts for 100% of all cases of malaria in Nigeria (WHO World Malaria Report 2017).

Clinical features of malaria

Signs and symptoms are usually non-specific and may not accurately predict malaria.

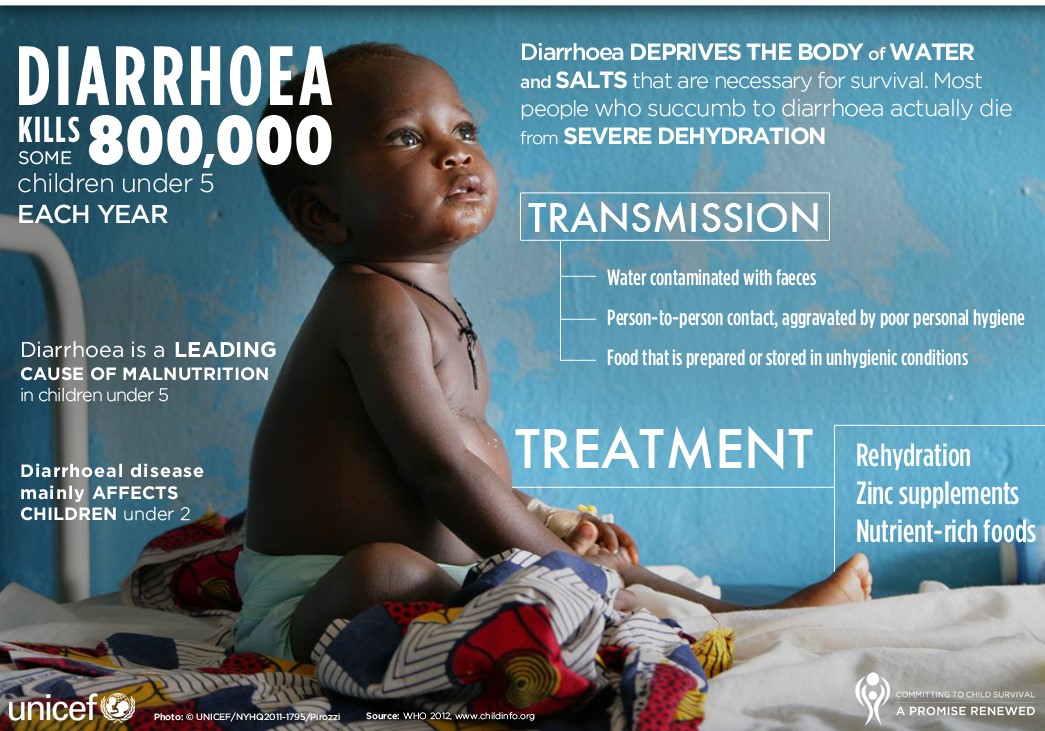

Uncomplicated malaria may present with the following: fever/sweats/chills, headache, malaise, body aches & pain, diarrhoea, nausea & vomiting, anorexia, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly.

Presence of one or more of the following may be indicative of severe falciparum malaria, in the absence of an identified alternative cause, and in the presence of P. falciparum asexual parasitaemia.

- Impaired consciousness: A Glasgow Coma Score <11 in adults or a Blantyre Coma Score <3 in children

- Prostration: Generalized weakness so that the person is unable to sit, stand or walk without assistance

- Multiple convulsions: More than two episodes within 24hours

- Acidosis: A base deficit of >8 meq/L or, if unavailable, a plasma bicarbonate of <15mmol/L or venous plasma lactate > 5 mmol/L. Severe acidosis manifests clinically as respiratory distress: rapid, deep and laboured breathing

- Hypoglycaemia: Blood or plasma glucose <2.2mmol/L (<40mg/dL)

- Severe malarial anaemia: A haemoglobin concentration < 5g/dL or a haematocrit of < 15% in children <12 years of age (<7g/dl and <20% respectively in adults) together with a parasite count >10,000/μL

- Renal impairment: (acute kidney injury): Plasma or serum creatinine >265μmol/L (3mg/dL) or blood urea > 20 mmol/L

- Jaundice: Plasma or serum bilirubin > 50μmol/L (3mg/dL) together with a parasite count >100,000/ μL

- Pulmonary oedema: Radiologically confirmed, or oxygen saturation <92% on room air with a respiratory rate >30/minute, often with chest indrawing and crepitations on auscultation

- Significant bleeding: including recurrent or prolonged bleeding from nose, gums or venepuncture sites; hematemesis or melaena

- Shock: Compensated shock is defined as capillary refill ≥3 seconds or temperature gradient on the leg (mid to proximal limb), but no hypotension. Decompensated shock is defined as systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg in children or < 80 mm Hg in adults with evidence of impaired perfusion (cool peripheries or prolonged capillary refill)

- Hyperparasitaemia: Red blood cell P. falciparum parasitaemia >10%

In regions with high inoculation rates like Nigeria, it is possible to develop partial immunity to the disease from early childhood. Young children who have not developed immunity to the disease are therefore at greater risk of suffering severe malaria. Other risk factors for severe malaria include pregnancy, elderly, HIV/AIDS, and Nigerians who reside in non-endemic areas.

Malaria is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. It causes absenteeism in school children and can impair a child’s development and learning.

Key recommendations for malaria treatment and prevention

- Diagnosis: prompt parasitological diagnosis by microscopy or rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) is required in all patients suspected of malaria before treatment

- Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is recommended as first-line curative treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria and should be given for at least 3 days. For maximum benefit, ACTs should be administered within 24-48 hours of the onset of malaria symptoms

- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) is medicine of choice with Artesunate-Amodiaquine (AS-AQ) as alternate

- Avoid monotherapy, it promotes resistance. Artemisinin and its derivatives should not be used as monotherapy for uncomplicated malaria. They are rapid-acting and if used alone, can lead to development of drug resistance. Nigeria has banned all oral artemisinin-based monotherapies (oAMT) since 2009.

- Chloroquine and Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine are no longer recommended for the treatment of malaria in Nigeria due to the prevailing high levels of resistance which have compromised their efficacy even in combinations.

- In pregnancy, the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in the first trimester is Quinine + Clindamycin given for 7 days. ACT may be used if Quinine is not available.

- In the second and third trimesters, ACT (AL or AS-AQ) is the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria

- In breastfeeding mothers, ACT (AL or AS-AQ) is the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria

- Treat infants weighing <5 kg with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria with an ACT at the same mg/kg bw target dose as for children weighing 5 kg; under supervision by a health care provider.

- Severe malaria is a medical emergency. The recommended first-line treatment for severe P. falciparum malaria is IV Artesunate. If parenteral Artesunate is not available, IM Arthemeter or IV/IM Quinine may be used as alternatives.

- Severe malaria must be treated parenterally for minimum of 24 hours, irrespective of patient being able to tolerate oral medication earlier. Treatment is completed by giving a full 3-day course of ACT.

- In treating severe malaria, children weighing ≤20 kg should receive a higher dose of artesunate (3 mg/kg bw per dose) than larger children and adults (2.4 mg/kg bw per dose) to ensure equivalent exposure to the drug

- In pregnancy, the first-line treatment for severe malaria is IV Artesunate

- Pre-referral treatment of severe malaria and prompt referral are recommended at the community or peripheral health facilities. The treatment options in order of preference include: •For children: artesunate IM; or rectal artesunate; or artemether IM; or quinine IM. •For adults: artesunate IM; or artemether IM; or quinine IM

- Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine can be used for the intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnant women (IPTp). SP should be given twice in pregnancy separated by at least 4 weeks, 1st dose to be given from 16 weeks of pregnancy. SP must not be used in the 1st trimester of pregnancy. The guideline recommends that since SP is an antifolate, the high-dose folic acid should be withheld for one week after SP administration

- The recommended chemoprophylaxis for non-immune visitors to Nigeria are: Mefloquine and Atovaquone-Proguanil. Doses should be taken prior to arrival in Nigeria and continued during the stay and following departure from the country.

- Malaria can precipitate crises in sickle-cell disease. Recommended treatment is ACTs and prevention is by vector control measures such as LLINs (long-lasting insecticidal nets).

- Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) is defined as the intermittent administration of full treatment courses of an antimalarial medicine during the malaria season to prevent malarial illness by maintaining therapeutic antimalarial drug concentrations in the blood throughout the period of greatest malarial risk. WHO recommends SMC for children aged 3 to 59 months living in areas of high seasonal malaria transmission. In Nigeria, SMC is recommended in States like Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara, Katsina, Kano, Jigawa, Bauchi, Yobe and Borno.

- Antipyretic measures are recommended for fever ≥38.5°C (101.3°F) using Paracetamol; tepid sponging is also advised for children.

- Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs): sleeping under insecticide-treated nets to prevent infectious mosquito bites.

- 21. Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS): indoor application of long-lasting chemical insecticides to kill malarious mosquitoes.

Goals of treatment

Malaria is an entirely preventable and treatable disease. The goals of treatment include:

- Rapid and complete elimination of the Plasmodium parasite from the patient’s blood in order to prevent progression of uncomplicated malaria to severe disease or death,

- Prevent chronic infection that leads to malaria-related anaemia.

- Reduce transmission of the infection to others, by reducing the infectious reservoir,

- Prevent the emergence and spread of resistance to antimalarial medicines.

Importance of diagnostic testing

Patients with suspected malaria should have parasitological confirmation of the diagnosis with either microscopy or rapid diagnostic test (RDT) before antimalarial treatment is started. Treatment based on clinical grounds should only be given if diagnostic testing is not immediately accessible within two hours of patients presenting for treatment. Prompt treatment – within 24 hours of fever onset – with an effective and safe antimalarial is necessary to prevent life-threatening complications.

Treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria

ACTs are the recommended first-line treatments for uncomplicated falciparum malaria. The artemisinin derivative components of the combination must be given for at least three days for an optimum effect. Artemisinin and its derivatives should not be used as monotherapy. Fixed-dose combinations are highly preferable to the loose individual medicines co-blistered or co-packaged.

First line treatment:

Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) as a fixed close combination (FDC) given twice daily for three consecutive days with the second dose being given eight hours after the first.

Detailed Dosage Schedule for Artemether/Lumefantrine – see under the drug monograph

Alternate first-line treatment:

Artesunate + Amodiaquine (AS+AQ): Given once daily for three (3) consecutive days. Available as a fixed-dose combination (FDC) and also as co-blistered packs containing the partner drugs as separate tablets

Detailed Dosage Schedule for Artesunate + Amodiaquine – see under the drug monograph

Other ACTs available for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria:

- Artesunate-Mefloquine;

- Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine;

- Artemisinin-Piperaquine

Second line treatment

The current guideline does not state a second-line treatment for uncomplicated falciparum malaria; it only stated an alternate first line.

Management of treatment failures

Recurrence of P. falciparum malaria can result from reinfection, or recrudescence (i.e., treatment failure). It may not be possible to distinguish recrudescence from re-infection. However, if fever and parasitaemia have not resolved or recur within 4 weeks of treatment, it should be considered as treatment failure with currently recommended ACTs. Treatment failures may result from:

- Drug resistance

- Poor adherence or inadequate drug exposure (e.g., due to under-dosing, vomiting or unusual pharmacokinetics in an individual), or

- Substandard medicines.

Find out if the patient vomited the previous treatment or did not complete a full course of treatment. If possible, confirm treatment failure by microscopy. In many cases, treatment failures are missed because patients who present with malaria are not asked whether they have received anti-malarial treatment within the preceding 1–2 months. This should be a routine question in patients who present with malaria.

Treatment failure within 28 days of receiving an ACT: In the absence of other causes of fever, and in the presence of persistent asexual parasites, the patient should be treated with the alternative medicine; in the case of AL, treat with AS-AQ and vice versa.

Treatment failure after 28 days of initial treatment: Treat as a new infection with the First-line ACT (i.e., AL or AS-AQ).

NOTE: Reuse of Mefloquine within 60 days of first treatment is associated with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric reactions and, in cases where the initial treatment was AS+MQ, second-line treatment not containing Mefloquine should be given instead.

Managing malaria in special populations

Uncomplicated malaria in pregnancy:

- Treat pregnant women with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria during the first trimester with 7 days of quinine + clindamycin. However, use an ACT if quinine is not available, or it is not possible to ensure/guarantee adherence to complete 7-day treatment with quinine

- Quinine is administered orally as 10 mg/kg body weight to a max. dose of 600 mg every 8 hours for 7 days.

- ACTs can be used in 2nd & 3rd trimesters. May be used in 1st trimester if Quinine is not available.

Malaria in young infants (<5 kg):

- Treat infants weighing <5 kg with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria with an ACT at the same mg/kg bw target dose as for children weighing 5 kg

- Paediatric formulations of ACTs e.g., paediatric Coartem (AL) or AS+AQ FDC – see under the drug monographs for the dosing details

Treatment of severe malaria

Severe malaria is a medical emergency requiring in-patient care. After rapid clinical assessment and confirmation of the diagnosis, parenteral treatment should be started without delay.

The primary objective of antimalarial treatment in severe malaria is to prevent the patient from dying. The secondary objectives are the prevention of disabilities and occurrence of recrudescence.

The antimalarial medicine recommended for the treatment of severe malaria in Nigeria is injectable (IV/IM) Artesunate. Where this is not readily available, intramuscular Artemether or intravenous/ intramuscular Quinine can be used as alternatives.

In treating severe malaria, children weighing ≤20 kg should receive a higher dose of artesunate (3 mg/kg bw per dose) than larger children and adults (2.4 mg/kg bw per dose) to ensure equivalent exposure to the drug

Recommended dosing for IV/IM Artesunate:

- For children ≤20kg, artesunate 3 mg/kg BW IV or IM given on admission (time = 0), then at 12 h and 24 h, then once a day is the recommended treatment.

- For adults and children >20kg, artesunate 2.4 mg/kg Body Weight (BW) IV or IM given on admission (time = 0), then at 12 h and 24 h, then once a day is the recommended treatment.

There is no upper limit to the total dose of artesunate.

Alternate regimen for treating severe falciparum malaria

Artemether, or Quinine, is an acceptable alternative if parenteral artesunate is not available:

- Artemether 3.2 mg/kg BW IM given on admission then 1.6mg/kg BW per day; or

- Quinine 20 mg salt/kg BW on admission (IV infusion or divided IM injection), then 10 mg/kg BW every 8 h; infusion rate should not exceed 5 mg salt/kg BW per hour.

Give parenteral antimalarials in the treatment of severe malaria for a minimum of 24 hours, once started (irrespective of the patient’s ability to tolerate oral medication earlier), and, thereafter, complete treatment by giving a complete course of the recommended ACT. ACTs containing Mefloquine should, however, be avoided if the patient had cerebral malaria because of the increased risk of seizures, encephalopathy and psychosis.

Pre-referral treatment

The risk of death from severe malaria is greatest in the first 24 hours. To survive, a patient with severe illness must get access rapidly to a health facility where parenteral treatment and other supportive care can be given safely and as appropriate. At community or health facility levels where complete management of severe malaria is not possible, patients with severe malaria should be given pre-referral treatment and referred immediately to an appropriate facility for further treatment.

The following options for pre-referral treatment are recommended in order of preference:

- For children: Artesunate IM; or rectal Artesunate; or Artemether IM; or Quinine IM.

- For adults: Artesunate IM; or Artemether IM; or Quinine IM

Intramuscular pre-referral treatment

- Artesunate 2.4mg/kg single dose

- Artemether IM 3.2 mg/kg single dose

- Quinine dihydrochloride at a dosage of 10 mg/kg salt diluted to 60mg/ml intramuscularly at the anterolateral aspect of the thigh given at divided sites

Intra-rectal pre-referral treatment

Artesunate suppositories: Single dose to be administered rectally; expelled from the rectum within 30 minutes of insertion, a second suppository should be inserted and, especially in young children, the buttocks should be held together, or taped together, for 10 minutes to ensure retention of the rectal dose of artesunate.

Recommended dosing: (Usually available as 50 mg or 100 mg suppositories)

<10 kg (<12 months): 50 mg as a single dose

10-19 kg (1-5 years): 100 mg as a single dose

20-29 kg (6-9 years): 200 mg as a single dose

30-39 kg (10-13 years): 300 mg as a single dose

>40 kg (>13 years): 400 mg as a single dose

Alternate intra-rectal pre-referral treatment:

- Artemether Intra-rectal 10-40mg/kg single dose, OR

- Quinine Intra-rectal 12mg/kg single dose

These should be administered with a syringe without the needle.

Treatments not recommended for management of severe malaria

The guideline does not recommend the use of the following drugs in the treatment of severe malaria:

- Corticosteroids and other anti-inflammatory agents

- Agents used for cerebral oedema e.g. Urea

- Adrenaline

- Heparin

Chemoprevention and chemoprophylaxis of malaria

Malaria prophylaxis is generally not necessary in persons living in a malarious area because it may lower one’s resistance to the disease. Prophylaxis should, however, be used in sickle cell anaemia and in non-immune visitors because of risk for severe disease, but it is not 100% protective. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy is recommended for all pregnant women.

Children and adults with sickle cell anaemia

Individuals, both children and adults, with sickle cell anaemia are widely recognised to be at increased risk of sickle cell crisis from malaria infections. Sleeping under the Long Lasting Insecticide Nets (LLIN) is generally recommended. The current guideline does not recommend any medicine for chemoprophylaxis in this population. Persons living with sickle cell anaemia who suspect malaria should report to the health facilities for prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Chemoprophylaxis for non-immune visitors/residents

Non-immune visitors to areas of malaria transmission are at high risk of malaria infection. In addition to the provision of information concerning effective measures to reduce human-mosquito contact, non-immune visitors to Nigeria should also be given chemoprophylaxis. The following options are recommended for use in Nigeria:

- Mefloquine, and

- Atovaquone-Proguanil

Doses should be taken prior to arrival in Nigeria and continued during the stay and following departure from the country.

Recommended dosing: see under the Mefloquine and Atovaquone/Proguanil monographs

Recommendations for intermittent preventative treatment in pregnancy (IPTp)

Malaria risk is higher during pregnancy and may be asymptomatic. In line with WHO recommendations, Nigeria implements the following interventions for the prevention and treatment of malaria in pregnancy:

- Use of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs)

- IPTp with SP

- Prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of malaria illness.

Intermittent Preventive Treatment (IPT) with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine (SP) reduces malaria-related complications during pregnancy. The guideline recommends that SP shall be administered as part of the antenatal care (ANC) package with other components including anthelmintics in the second or third trimester, nutrition counselling, and daily hematinic supplements (iron and low dose folic acid). It further states that high-dose folic acid when used, should be withheld for one week after SP administration due to the antifolate activity of sulfonamides.

Recommended dosing: SP should be given as a single adult dose of 3 tablets (each tablet contains 500 mg Sulfadoxine + 25 mg Pyrimethamine) at scheduled antenatal care visits. Three (3) or more doses given one month apart are currently recommended. First dose should be given after quickening (early second trimester or following the onset of the first foetal movement).

Pregnant women, who are HIV positive and are on Co-trimoxazole chemoprophylaxis, should not receive IPT with SP, due to the increased risk to the adverse effects of the Sulfonamides.

The use of Long Lasting Insecticide Nets (LLINs) should be promoted as an additional preventive measure.

Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC)

Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) is defined as the intermittent administration of full treatment courses of an antimalarial medicine during the malaria season to prevent malarial illness by maintaining therapeutic antimalarial drug concentrations in the blood throughout the period of greatest malarial risk.

SMC is recommended in areas of highly seasonal malaria transmission throughout the Sahel sub-region. The target areas should be those where malaria transmission and majority (>60%) of clinical malaria cases occur during a short period of about 4 months. In Nigeria, SMC is recommended in States like Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara, Katsina, Kano, Jigawa, Bauchi, Yobe and Borno.

WHO recommends SMC using a full course of Sulfadoxine/Pyrimethamine + Amodiaquine (SP+AQ) once a month for max. 4 months during the malaria transmission season for children aged between 3 and 59 months.

Recommended dosing: see under the Sulfadoxine/Pyrimethamine + Amodiaquine (SP+AQ) monograph

Further reading:

- Nigeria 2015 National Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Malaria May 2015.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.severemalaria.org/sites/mmv-smo/files/content/attachments/2017-02-06/Nigeria%202015%20National%20Guidelines%20for%20Diagnosis%20and%20Treatment%20of%20%20Malaria%20%20%20May%202015.pdf

- WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, 3rd Edition [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 20]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/162441/9789241549127_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- World Malaria Report 2017 [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 30]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259492/9789241565523-eng.pdf;jsessionid=C85143F42E96E3D58EE4ACC8A3B1CE4D?sequence=1

In pregnancy, the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in the first trimester is Quinine + Clindamycin given for 7 days. ACT may be used if Quinine is not available.

In pregnancy, the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in the first trimester is Quinine + Clindamycin given for 7 days. ACT may be used if Quinine is not available. In breastfeeding mothers, ACT (AL or AS-AQ) is the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria

In breastfeeding mothers, ACT (AL or AS-AQ) is the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria